orlow

orlow

Orphans, giants, and your disappearing digital rights

They’re at it again. Who? Take a guess: if it’s not the Daily Mail, then it’s probably the BBC. The corporation has once again been caught pinching photos, wrongly attributing them, and pretending nothing ever happened – in a triumph of crowd-sourced “citizen journalism”.

But this incident of photo-lifting is slightly more noteworthy than most: the BBC used a photograph taken nine years ago in Iraq to illustrate its story about the massacre at the weekend in Syria.

Shoreditch’s sparkle leaves BBC presenter ‘tech-struck’

“I haven’t felt so good having spoken to a businessman for ten minutes in about 25 years. That’s not normally how I feel! So thanks very much!”

And thanks to you, BBC presenter Fi Glover, for sharing the feel-good factor with us.

Glover was bringing the miracle of Shoreditch’s internet companies into the nation’s living rooms as part of a mission for Radio 4’s One to One slot. She had vowed to find out, in her words, “what do these tech-enabled business zoomers do”.

We learned that “while the rest of this country hangs onto the cliff face of economic prosperity by its fingernails, it seems that many of these internet-savvy people are right on top of the cliff, planting a flag”.

We need more flags on cliffs.

Popper, Soros, and Pseudo-Masochism

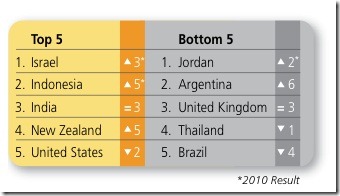

A new report by intellectual property campaigners has again put the UK on the naughty step.

This year, as last year, activists list the UK alongside Brazil and Thailand as having the most “oppressive” copyright laws in the world. The report was published by an international NGO called Consumer International, but this delegates the work out to a Soros-funded group called A2K.

It’s certainly a bold point of view. How does it arrive at this conclusion? Helpfully, we have the founder’s testimony to aid us.

A2K Network’s world view is that “publicly owned” knowledge is good, but “privately owned” knowledge is bad. It considers this a binary, zero-sum choice – and it is also one that trumps all other considerations.

So, by A2K’s yardstick, it doesn’t matter if the knowledge is easily accessible to citizens. It doesn’t matter, either, if a wide range of cultural material is available: a plurality of goods. Or that all this material is accessible to us at a low cost. Private ownership is the most important factor in any consideration; private ownership is evil.

Compulsory coding in schools: The new Nerd Tourism

The writer Toby Young tells a story about how the modern 100m race is run in primary schools. At the starting pistol, everyone runs like mad. At the 50m point, the fastest children stop and wait for the fatties to catch up. Then all the youngsters walk across the finishing line together, holding hands.

I have no idea if this is true – it may well be an urban myth. But the media class’s newly acquired enthusiasm for teaching all children computer programming is very similar.

Speaking as a former professional programmer myself, someone who twenty years ago was at the hairy arse end of the business working with C and Unix, I can say this sudden burst of interest is staggeringly ignorant and misplaced. It’s like wearing a charity ribbon to show how much you care. And it could actually end up doing far more harm than good.

Copyright on languages and APIs: why it’s a bad thing

Computer languages and software interfaces may fall under copyright protection if Oracle succeeds in its Java lawsuit against Google. Amazingly, “copyfighters” appear to have paid little or no notice to this rare extension of copyright into new realms. But the consequences and costs for the software industry could be enormous.

A short history of “Breaking the Internet”

“I am the head of IT and I have it on good authority that if you type ‘Google’ into Google, you can break the Internet. So please, no one try it, even for a joke. It’s not a laughing matter. You can break the Internet”

– Jen, The IT Crowd

For 15 years internet companies have been waging a war against any kind of laws that establish properties and permissions for digital things. Every attempt to do so has been bitterly fought. It’s the one constant in Silicon Valley’s battles against the copyright industries. The fight has crippled the traditional, historical partnership between technology and creators that benefited everyone. But it has also had an awful unintended consequence: it has weakened our ability to establish the clear property rights we need to protect our privacy.

When, in February, the EU tentatively suggested rules based on the principle that people own their own data, and this property right includes exclusivity (“the right to be forgotten”) – guess who was firing all guns against it? Facebook and Google… At Davos, Google chairman Eric Schmidt said the EU proposal would “break the internet”.

Just this week the UK government caused a huge privacy storm when it floated the idea of making internet companies keep a record of all personal communications on the the internet. While it argued that it wanted to store “traffic” data, not the contents of communications, little would be exempt: emails, blog comments, Tweets and Facebook Likes.

And more alarmingly, this trove of information would be casually available to busybodies. In 2010 alone, public authorities submitted 552,000 requests for communications data under RIPA. We’ve already seen how local councils, for example, initiate surveillance operations using the Act.

RIPA is intended to prevent “serious crimes”, requiring necessity and proportionality. But councils have used it to tackle “serious crimes” such as smoking, and putting recycling in the wrong bag. Some even boast about it. The new store of electronic communications would add to the data available to them. It’s a huge intrusion by the state into business that isn’t its own.

At the same time, Facebook and Google operate their own global data collection systems, hoarding huge amounts of personal data. And this is merely the start. The regression models that Facebook and Google use to predict consumer behaviour for advertisers are exactly what law enforcement agencies dream can be put to use to predict crime or ‘deviant’ behaviour. In a 2012 rewrite of Philip K Dick’s Minority Report, the “Pre Crime Division” will not require mutants floating in tanks – just software.

Privacy is not a luxury, or an optional extra – a world without privacy raises all kinds of ethical issues, and everyday judgements made about us.

So how can we halt this slide to Panopticon, where everything we do online is dipped into?

Well, no matter what law you pass, it won’t work unless there’s ownership attached to data, and you, as the individual, are the ultimate owner. From the basis of ownership, we can then agree what kind of rights are associated with the data – eg, the right to exclude people from it, the right to sell it or exchange it – and then build a permission-based world on top of that. None of this is possible without the fundamental recognition that it’s the individual – you or me – who ultimately owns it, and ultimately decides what’s then done with it, and by whom. Without properties and permissions on digital “things”, there will be no digital privacy.

I’ll illustrate this with a short story that you probably haven’t heard before – about this great phrase.

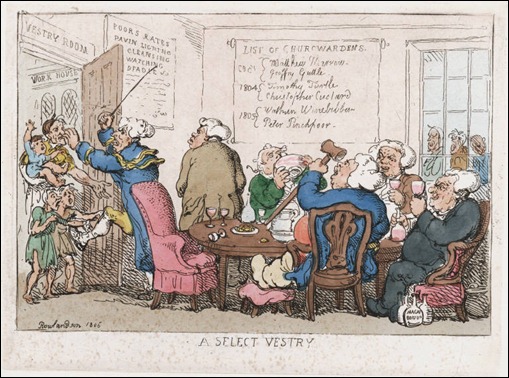

Indoor work relief for the middle classes

John Stuart Mill described the British Empire as “outdoor relief for the middle classes”. The phrase “indoor relief”, at the time, referred to the state-sponsored workhouse programme, which invented jobs for the poor to prevent them being idle. Mill was implying that the Empire was a gigantic job creation scheme.

But in the 21st century the British Empire appears to be resurrecting itself in a very strange and interesting new way. In response to a FOIA request from Leo Hickman, the Guardian’s ethical bloke, we learn of all the donations made for the purpose of climate energy projects by the Foreign Office (FCO).

And it’s fascinating reading.

Nature ISN’T fragile – nor a bossy mother-in-law

The Green movement needs to rethink its philosophy from the ground-up. That’s according to Peter Kareiva, a leading conservation expert and chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, the world’s biggest environmental group.

It must abandon the idea that nature is “feminine” and in particular that it’s “fragile”, he said, because not only is this artificial, it’s wrong, and so many bad ideas follow.

When people believe that a fragile “Mother Nature” is harmed by anything humans do, it’s actually the humans who suffer, Kareiva argues in the co-written essay called Conservation in the Anthropocene.

Environmentalism is now dominated by “misanthropic, anti-technology, anti-growth, dogmatic, purist, zealous, exclusive pastoralists” – says Kareiva. Greenpeace’s co-founder Patrick Moore made similar points in an interview here.

The modern environmental movement views every human action – from fracking to flying – as both intrinsically evil and irreversibly harmful. But this is an artificial view, one generated out of convenience, says Kareiva. “The notion that nature without people is more valuable than nature with people and the portrayal of nature as fragile or feminine reflect not timeless truths, but mental schema that change to fit the time,” the authors write.

Who killed ITV Digital?

After 25 years of watching the Murdoch TV empire unfold, the battle plan to beat him should be fairly obvious. You buy the best content – the most popular sport and movies – and raise lots of capital, and make watching it easy. Then you dig in for a very long fight.

In other words, this is the entertainment-business-as-usual. Wannabe telly and radio empires have failed because they bought the wrong stuff, were inconvenient to use or because they were under-capitalised in the long run – and typically it’s a mixture of all three. Entertainment isn’t an essential utility. It’s a discretionary purchase for households, and the market doesn’t tolerate inconvenience or rubbish for long.

But when the tale involves Rupert Murdoch, people will always look for diabolical reasons for his success. The myth demands it. A fascinating BBC Panorama researched by Guardian reporter David Leigh may give supporters of this view plenty of ammunition. It was enthralling TV about the TV biz, and must have been an eye-opening for anyone not familiar with the decade-old telly crypto saga. But for those of us familiar with the details and the context, the smoking gun just isn’t there. Murdoch’s telly rivals would have gone down even if nobody had ever watched a single one of their programmes for free.