How can we begin to unpick the tangled mess that the technology and creative industries have created?

There’s certainly no shortage of blame to go around. In the past every new wave of technology has delivered healthy creative markets – but today this is no longer happening.

Just 20 years since the birth of the internet economy, with the advent of the worldwide web, it’s worth asking why. It’s time we looked afresh at where both industries went wrong, and how they can get on the right track again.

Much of what follows will highlight key mistakes made – but before we do that, we need to put them in some historical context. What worked in the past is a fairly reliable indication of what can work again in the future.

The current impasse between technology and copyright sectors is certainly an odd one. Historically, war is the greatest driver of technological innovation of all, but in peacetime it’s the demand for culture and entertainment that spurs the most innovation. People want to see and hear stuff, and are prepared to pay for it.

The cash generated is ploughed into more entertainment – even creating new art forms. (Recall how the first movie dramas were starchy, filmed theatrical plays.) This creates more investment in technology so people can enjoy the entertainment in a better way. Round and round it goes.

At the heart of this virtuous circle, copyright has been the obscure back-room business-to-business mechanism that keeps the players honest. Creators demanded that their industries engage with the new technologies to create new markets, which returned more money for their talent.

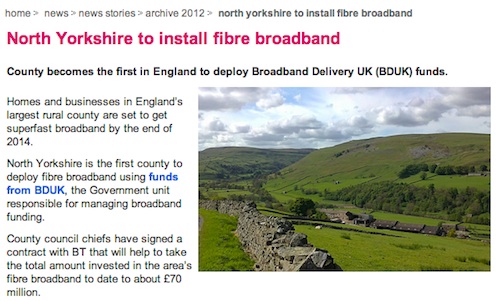

As a result technology innovators needed to attract talented creative people, and induce them to produce stuff for their kit: recording their music on long-players rather than shellac, or printing their movies in Technicolor™. So the two sides need each other. Technologists’ incentives were simple: create more amazing gear to deliver the best of other people’s stuff. And each wave of innovation grew the market, and ensured the creators and workers were richer. Remember: No innovation has ever made creative industries poorer.

Unfortunately, the truth of this historical mutual dependency gets forgotten today because the incentives aren’t lined up. Investment decisions in technology services are made without a thought for the health of the creative people who generate the demand for the goods. Creative investment decisions either don’t take advantage of the technology, or are hamstrung in a way that leaves the potential of the technology untapped. Things are also complicated by another factor we’ll call the Unicorn.

I’ll open the catalogue of errors at chapter one, the music industry.

Read more