When people buy software – buy it in seriously large amounts – it isn’t just today’s binary they’re choosing. They’re buying what they think is a bit of the future – they’re buying a piece of risk insurance. This explains why very mature and well-proven systems often lose out to the Newest Kid on the Block. It also explains the enduring effectiveness of FUD and Vapourware.

And it’s not just software. From TP monitors, to minicomputers, to Novell Netware, recent history is full of examples of perfectly splendid systems being thrown out and replaced with something that doesn’t live up to the billing – and perhaps never will. Which sounds wacky, but that choice is being made on the rational calculation that the software or hardware of choice today won’t be made or supported, or the standards that bind the parts of the system together will become obsolete. (Which leads to the same thing.)

Sometimes a brave company bucks the trend. Most famously Microsoft refused to “eat its own dog food”, and stood firm against the move to client/server computing running PC or Unix-based databases like Microsoft SQL Server, instead insisting that its mission-critical accounts department ran on, er, an IBM AS/400 mini.

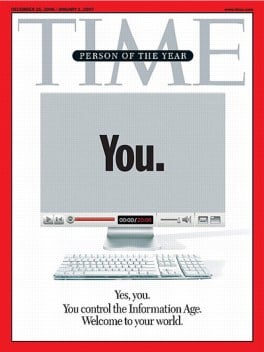

But by and large, the strategy works very well for companies that trumpet a “paradigm shift”, or “new era in computing”, and convince people that they own a secret part of the future – one that no one else can yet see. It worked for Microsoft, and Google hopes it will work for it, too. The Chrome browser today is little more than a piece of demoware, but it’s not just about “today”, is it?

Before we see what Google is hoping to achieve with Chrome, let’s take a look at a precedent from history that I find quite spooky.

Old-timers may excuse this brief wallow in nostalgia.

Read more