“I am the head of IT and I have it on good authority that if you type ‘Google’ into Google, you can break the Internet. So please, no one try it, even for a joke. It’s not a laughing matter. You can break the Internet”

– Jen, The IT Crowd

For 15 years internet companies have been waging a war against any kind of laws that establish properties and permissions for digital things. Every attempt to do so has been bitterly fought. It’s the one constant in Silicon Valley’s battles against the copyright industries. The fight has crippled the traditional, historical partnership between technology and creators that benefited everyone. But it has also had an awful unintended consequence: it has weakened our ability to establish the clear property rights we need to protect our privacy.

When, in February, the EU tentatively suggested rules based on the principle that people own their own data, and this property right includes exclusivity (“the right to be forgotten”) – guess who was firing all guns against it? Facebook and Google… At Davos, Google chairman Eric Schmidt said the EU proposal would “break the internet”.

Just this week the UK government caused a huge privacy storm when it floated the idea of making internet companies keep a record of all personal communications on the the internet. While it argued that it wanted to store “traffic” data, not the contents of communications, little would be exempt: emails, blog comments, Tweets and Facebook Likes.

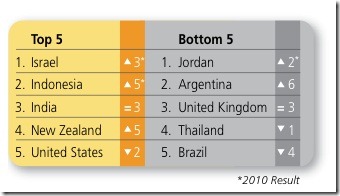

And more alarmingly, this trove of information would be casually available to busybodies. In 2010 alone, public authorities submitted 552,000 requests for communications data under RIPA. We’ve already seen how local councils, for example, initiate surveillance operations using the Act.

RIPA is intended to prevent “serious crimes”, requiring necessity and proportionality. But councils have used it to tackle “serious crimes” such as smoking, and putting recycling in the wrong bag. Some even boast about it. The new store of electronic communications would add to the data available to them. It’s a huge intrusion by the state into business that isn’t its own.

At the same time, Facebook and Google operate their own global data collection systems, hoarding huge amounts of personal data. And this is merely the start. The regression models that Facebook and Google use to predict consumer behaviour for advertisers are exactly what law enforcement agencies dream can be put to use to predict crime or ‘deviant’ behaviour. In a 2012 rewrite of Philip K Dick’s Minority Report, the “Pre Crime Division” will not require mutants floating in tanks – just software.

Privacy is not a luxury, or an optional extra – a world without privacy raises all kinds of ethical issues, and everyday judgements made about us.

So how can we halt this slide to Panopticon, where everything we do online is dipped into?

Well, no matter what law you pass, it won’t work unless there’s ownership attached to data, and you, as the individual, are the ultimate owner. From the basis of ownership, we can then agree what kind of rights are associated with the data – eg, the right to exclude people from it, the right to sell it or exchange it – and then build a permission-based world on top of that. None of this is possible without the fundamental recognition that it’s the individual – you or me – who ultimately owns it, and ultimately decides what’s then done with it, and by whom. Without properties and permissions on digital “things”, there will be no digital privacy.

I’ll illustrate this with a short story that you probably haven’t heard before – about this great phrase.

Read more

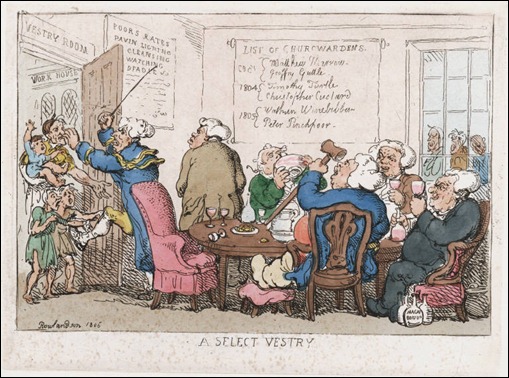

Spot the broadband user in this picture

Spot the broadband user in this picture